- Home

- Hazel Barkworth

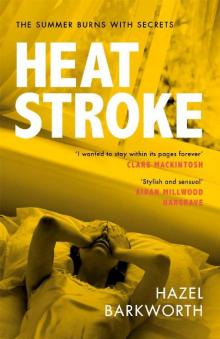

Heatstroke: an intoxicating story of obsession over one hot summer Page 5

Heatstroke: an intoxicating story of obsession over one hot summer Read online

Page 5

Then sinking down onto the seats and rocking gently as they sipped from the same bottle, their mouths tightened around the same circle. To drink from those bottles was a sort of kiss: lips on the glass, tongue stoppering it. It created the kind of drunk that transports, makes the world an entirely different place. It was the kind of drunk that made her able to dance.

She could leap there; she could turn cartwheels by the bright, false lights. Streetlamps had never looked so glamorous. She pulled herself up onto the climbing frame with strength she didn’t know her arms had; heaved her whole body skywards, hooking her legs over the metal rods, letting herself hang, impossibly, in the night. His voice reached her upside-down ears, singing every word of ‘Spaceball Ricochet’. Then straddling the frame, her thighs taut, her arms up in the air at the beat of the soundtrack coming from his car. She is a changeless angel, she’s a city, it’s a pity that I’m like me.

Her hair was loose, and tangling in the breeze, and every song was written about her. He was looking at her; he was watching.

Then they lay, sprawled on the asphalt. No one in the world knew where they were. The night crept darker, and the tarmac was cool against the backs of her legs. She could taste the antiseptic tang of alcohol on his mouth. Her fingers, filthy from the ground, were in his hair. They barely spoke, but kissed. His hands on her face, her waist, her legs. They kissed like adults can’t kiss: where the kiss is everything there is; where there is no thought of whatever might come next.

Rachel headed to the gym on nothing but autopilot. She only ever had forty-five minutes. Three times a week. She’d contort her already jammed days to fit it in. It had to be regimented: twenty-five minutes on the treadmill, then twenty on the static bike. Afterwards, she’d shower, dab on lipstick and eyeliner – smudging both to make them look worn in – then head straight to school.

She made the most of her time that morning, eschewing a warm-up and starting as close to full pelt as possible, pumping her legs up and down. Up and down. It was sluggish at first, slow and uncomfortable. She debated stopping, leaving, getting a coffee instead, but then it eased. Whatever stickiness lay in her muscles turned to oil, and the movements suddenly flowed naturally. As soon as it was fluid, she pushed herself harder. Hard enough that it hurt. Harder than she’d ever pushed. Her body was hers now. No other eyes saw its hidden parts; no other hands moved over it for weeks at a time. Her body, once so touched, so cherished, was now alone. Its shape and scent and taste belonged to no one else.

For forty-five minutes, Rachel focused on nothing but her movements. She played no music, tuned into no podcast, no television programme. She didn’t let herself think. Just move. Faster and harder until it felt like her veins would burst and her lungs might flood with blood. Sweat gathered on the crown of her head. She bowed her face down and closed her eyes. She could see nothing but the red behind her lids. When it reached the tipping point, when the weight of the pooled sweat was enough to send drips coursing down her nose, it felt like victory.

As Rachel drove into the car park, the school seemed invaded. It wasn’t yet eight, but two large vans sat squarely in the centre of the tarmac, logos proud on their sides, satellite dishes perched on top, crossing several parking bays each. The story had become juicy: the blonde girl, the distraught parents, the missing underwear. Lily Dixon was no longer a friend, a pupil; she was public property. Her name was known hundreds of miles away.

The people busily charging between the vans were all men. They looked different from the men who usually walked around the school. These men wore thick-rimmed glasses, lanyards round their necks, black T-shirts. They had stubble that sometimes thickened into beards. The equipment they held on their shoulders, or positioned on tripods, was enormous and professional. These images would be beamed all over the country. It looked like a film set. It was almost exciting.

Rachel slalomed her Corsa around them to get to her usual spot. There were at least ten men in the car park, and she’d have to wade through a throng to get to the door. She didn’t know how to greet them; should she smile, nod, stoically ignore? As they came into focus, she felt acutely aware of the peek of bra strap that was showing under her shirt, the painted toenails in her sandals.

She nudged the arm of a camera-carrying man as she squeezed by. ‘Hey, watch it.’ As he turned, the camera swooped to stare at her with its unblinking mechanical eye. Rachel felt the blood redden her cheeks.

‘Can you guys back off a bit?’ Rachel cringed at her use of the word ‘guys’, but the man just looked at her blankly. ‘The kids are freaked out enough.’

‘I’m sorry, but we’ve got permission. It’s totally legit.’

‘Permission to be here, not to be intrusive.’

He backed away from her, his one free palm raised in a gesture of mock-surrender. ‘It’s not my call, I’m afraid. We’re Sky News.’

Rachel knew how to talk to errant teens, but the same tone of voice deployed on a grown man sounded absurd. The slick of MAC Ruby Woo that usually gave her such swagger felt gaudy now, heavy on her lips.

‘A girl’s missing. Can you show some fucking respect?’ She spat the words out, then walked towards the school, every step placed carefully, so she didn’t stumble.

‘Have you seen this?’

It was all Rachel could do not to grab the paper from DC Redpath’s hand. The police detectives were the same, but the location was very different. DC Redpath. DC Scott. No longer nursing mugs in her living room, but stationed behind the deputy head’s desk with glasses of water placed officiously in front of them. With new evidence, they needed to question Lily’s friends further. Rachel was cast again as the chaperone.

She was eventually passed a copy. It was a printout of an Instagram screen. The blue strip at the top, the love hearts to show who had double-tapped their approval. The digital made physical looked uncanny. The image was a still from an old movie: black and white, a woman with pale, wavy hair that fell over one eye, sitting in a car with a scruffy man in a hat. Rachel didn’t know either of their names. Scrawled over the top in mock-handwriting, too perfect to have flown from human movements, was one word. Wanderlust. It had 129 likes.

‘Have you seen this before, Mia?’ The sing-song tone of their last meeting was gone.

Mia only shrugged. Her face was calm, but her breaths were jagged. ‘Yeah. It was on Lily’s Instagram the other week. She’s always putting crap like this on.’ Rachel could sense her daughter’s thrill at the mild swear word, and felt almost proud.

‘Did it seem significant to you?’

‘It’s the sort of thing she loves. She’s always making stuff like this.’

‘Do you know where the image is from?’

‘Some old film, I don’t know.’

DC Redpath coughed slightly, clearing her throat. ‘We haven’t found a note from Lily, as you know, Mia, but we do know that she packed a bag and took it with her. Her mum thought she was heading to your sleepover, but she never turned up, did she?’

It was barely a question. A flash of guilt jabbed Rachel’s veins. Should she have known something was amiss? Should she have called Debbie to alert her? The girls had seemed unconcerned, and hardly commented on Lily’s absence. But they were only fifteen.

‘We need to know where she might have gone instead. Do you know what “wanderlust” means?’

Mia’s eyes closed. ‘Wanting to travel.’ Rachel was impressed. She had no idea where Mia had picked up the concept.

‘Yes. Exactly. It means a strong, innate desire to travel.’ In the detective’s mouth it sounded mechanical, like she’d learned it by rote. ‘Does she ever talk about running away?’

A sigh now, heavy, shaking. ‘She talks about wanting to go places, but we figure she means after sixth form.’

‘Who is we?’

‘All of us, we all talk about things like that. We talk about everything.’

‘Where does she want to go?’

‘Hollywood, I suppose. She’s always posting pictures of films.’

‘Do you know where she might have gone?’

Mia shook her head ever so slightly. She was giving nothing away, if there was anything at all to give.

‘Do you know who she might be with?’

Another shake. Rachel knew they had checked every register. No boys from their school were absent without reason. Everyone had arrived at every lesson, every exam. But there were other boys, and other ways to meet them. Lily had been in plays outside of their drama studio.

‘Does she have a boyfriend?’

Mia’s head shook again. Rachel felt the disappointment; the breath she held still couldn’t be released. A boyfriend would answer everything. Some boy from another school she’d met at Friday-night theatre club. Some boy she’d been seeing secretly for months. Some older boy who’d convinced her to sneak away for a few days; some boy she wanted to impress with her bravery, her spontaneity, her lingerie.

‘Is there any boy she talks about?’

Mia swallowed. ‘Lily isn’t really like that.’

A brisk nod. ‘Is there anyone she particularly likes, though?’

‘She isn’t like that. She doesn’t talk about boys she fancies.’

DC Redpath’s voice was deeper now. ‘Mia, do you have any idea at all who Lily might be with, or where she might be?’ The questions, asked again, stuck in the air.

Mia shrugged, her shoulders flicking up and down. ‘I really don’t. I don’t know where she is.’

He had spun the metal that night. He’d heaved it with strong arms, gripping the railings, then releasing, to lurch the roundabout into ragged circles. She had forced her eyes to stay open, and caught a flash of him with every cycle. Him. Him. Him. Him. The whirling had caused the earth to jink on its axis over and over. Stop it! Stop it! She’d screwed her eyes tight, and there’d been no way of knowing which was up or down. Everything had blurred.

When the speed seemed almost frightening, he leapt on with her, propelling himself in one movement. They both clung to the metal and faced each other. The rest of the world had faded to a dizzy, sickening whirr, and she was unable to see anything but his face, grimacing against the speed, the centrifugal force. The neon whirl of the world eventually slowed, in wobbling revolutions; slowed to the speed of his records, thirty-three and one third rotations per minute, the speed where the needle could dip into the grooves, bobbing and nodding until sound miraculously formed, until plastic turned to noise. They’d looped slower, slower, slower, then circled to a close, a halt that shocked them with its stillness.

‘What can we do without Lily?’

The drama studio was dark, and several degrees cooler than the rest of the building. After a morning of lessons, Rachel felt the relief of being around only two other people.

‘Will someone else play Laura?’

Rachel felt her shoulders relax for the first time in days as she told the truth. ‘You know what, I don’t know, Dominic. I really don’t know. I suppose we’re going to have to give it a few days. See what happens.’

‘Yeah, this might all be nothing, right?’

Last year’s summer show had been a fifty-four person, all-singing-and-dancing spectacle of Oliver! that Rachel had assisted the head of drama in staging. She’d spent long weeks sourcing scores of butcher-boy caps and drilling the cast in awkward pas de bourrée. When it was her turn, she’d opted for something more intimate. This year didn’t need a major event. A cast of four was enough. Briony Havering in Year 11 did such an accurate southern drawl in her audition that the part of Amanda could go to no one else; Ross Pike was a solid, handsome Tom, and the other two roles were students Rachel knew well – Dominic, Keira’s brother, as Jim, the Gentleman Caller, and Lily as Laura Wingfield.

When Briony and Dominic turned up at lunchtime as scheduled, Rachel could scarcely contain her gratitude. The room felt almost normal.

‘As you guys are both here, do you want to run lines? We can only really do scene seven, but it might be worth a go?’ They had barely opened their battered, highlighted texts before Graham strode in. Rachel had never seen him in the drama wing before.

‘So, actors, how goes the “menagerie of glass”?’ His eyebrows added the quotation marks around the words. Rachel sensed the phrase was rehearsed but hadn’t come out quite how he’d intended. His face rearranged as he seemed to realise the tone he’d struck was all wrong. He was suddenly grave, turning to face Dominic and Briony. ‘Well done, you two, well done. You really are doing exactly the right thing. We need to keep going, to keep our chins up.’ They both nodded without smiling.

He steered Rachel a few steps away, his hand glancing her elbow. She could feel the warmth from his skin.

‘How are the students holding up?’

Rachel couldn’t muster the energy to lie. ‘They’re rattled. What else can you expect?’

‘Of course. I understand. Your response seems spot on. We have to steer them through this in the right direction.’

‘But we’re all rattled as well. And how do you know if you’re picking the right direction, or steering them down one that will seem fucked up in a week’s time?’

He seemed to stiffen at the challenge, at the language. Rachel knew she’d gone too far. She didn’t wait for him to reply.

‘How are the police doing? Have you heard any more?’

‘No, nothing. They’re doing everything they can. We’re just hosting, to be honest. You’ll be the first person I contact when we hear from them. I know you were close to Lily. This must be very hard for you.’

Rachel felt her throat tighten at his words.

Rachel could see the screen, but not clearly. Five or six of them were crowded around Cressida’s laptop in the staffroom. The footage was on the BBC News website. It was only a few seconds, but Cressida kept clicking it to repeat.

The screen filled with black and white at first, as if the connection had been lost. Then a ghostly figure danced across the top right corner. It was CCTV footage. Cressida made it perform those same steps over and over. The images had been taken from the security cameras of a small shop in a ferry port, hours away. Lily was walking towards the counter to pay. She had an armful of bottles and packets. Rachel knew for certain it would be Diet Coke and Starmix.

‘It’s her.’ Cressida had watched it scores of times, but still sounded awed.

Lily was alive in those seconds of film. Her strong, vital legs were pumping across the screen, propelling her forwards. She was wearing black leggings and ballet shoes. Despite the heat, her coat was slung over one arm.

Lily had been in a ferry terminal. She would be hundreds of miles away now, an ocean away. Rachel leaned over and stopped Cressida’s hand.

‘Let it play to the end.’

The newscaster spoke for a moment, solemn words Rachel couldn’t make out. Then another burst of footage. It was as flecked and grainy as before, but there was a figure by the door, holding it open, waiting for Lily. A figure in the shadows, unidentifiable, but clearly male.

Cressida emitted a stifled gasp. Rachel rested her hands on the younger woman’s shoulders, on the thin, green cotton of her blouse. She was grateful for someone to comfort.

Lily had been timid around Briony and Ross. They were in the year above, and Rachel had noticed how Lily rarely approached them. She’d sit on her own at rehearsals, staring at lines she’d already memorised until Dominic arrived. Sometimes she’d hardly speak in her own words, relying entirely on Tennessee Williams. Her own accent would be silent for the whole evening, but Laura’s drawl would arrive at all the right moments. It was a blessing that her most charged scenes were opposite Dominic. The interchanges between Laura and Jim were the hardest to nail.

‘I wanted to ask you to – autograph my program

me.’ Lily’s voice was soft as Laura.

‘Why didn’t you ask me to?’

Lily would ask questions just to Rachel after each run-through.

‘He’s older than her, isn’t he?’

‘Jim? No, I think they’re the same age. If you remember, he talks at one point about being twenty-three, and she says she’s twenty-four soon.’

‘But she seems younger.’

‘Okay.’

‘It’s not always just about actual age, is it? And she’s so impressed by him.’

Lily’s eyes had been wide with an odd kind of intensity. Rachel had made sure not to disregard her. ‘How do you think that might make her feel?’

‘Intimidated, maybe?’

Lily had paused, but Rachel hadn’t wanted to interrupt her thoughts.

‘I actually think she feels really flattered. That this impressive man is paying her so much attention. He doesn’t have to, does he? But he can obviously see something in her that her family or her friends don’t. There is something about her he really likes. That must feel nice for her. It must make her feel special.’

It was the most Lily had ever said in a rehearsal. The others had stopped to listen. Rachel had felt a prickle on her skin, under her skin. Sweat had pooled in the mass of hair held at her nape. She’d nodded at Lily. Then, she’d dismissed the unease as no more than heat and stress; no more than the tickle of sweat as it made a slow journey down her spine.

‘You need to relax, Debs, you need to sleep. You must be exhausted.’ Rachel cooed the words, extending the vowels, stroking Debbie’s head with every phrase, combing fingers through her hair. It left an oily sheen on Rachel’s palms. Showering must be the last thing on Debbie’s mind. Rachel eased the coffee mug – pink, a cartoon girl dancing by a cartoon rainbow – from Debbie’s hands.

Heatstroke: an intoxicating story of obsession over one hot summer

Heatstroke: an intoxicating story of obsession over one hot summer