- Home

- Hazel Barkworth

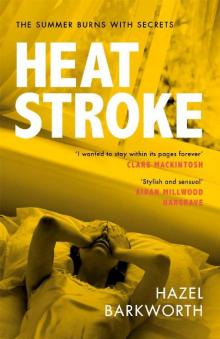

Heatstroke: an intoxicating story of obsession over one hot summer Page 2

Heatstroke: an intoxicating story of obsession over one hot summer Read online

Page 2

The sponge was disintegrating under the effort. Rachel threw it in the bin, and grabbed a fat, unopened packet of wipes from the cupboard. She broke the seal with too much force and sent all eighty wipes spilling over the floor, then snatched handfuls of them. They came away filthy. The floor looked clean, but the grime must have been all around them, filling their lungs with every breath. Rachel couldn’t bear it. The house needed to be clean for when Mia came home. She scrubbed. It was too hot for that kind of vigour, but she scrubbed anyway, ignoring the dizzy blackness that fogged her head. She scrubbed until her knuckles were raw, until sweat dripped into her eyes; scrubbed without stopping, without thinking, until Mia’s key grated in the lock.

Rachel squeezed teabags against the side of the mugs they hardly ever used: the ones that were a gift from her mother, the ones that matched. She placed the spent bags into a china dish. Her hands were weak. It was too hot for tea, but she’d offered and they’d accepted. The kitchen shone. She stirred in their milk and one sugar, chinking a teaspoon and setting her face to mild.

Rachel perched on an armchair as they spoke, nothing but a chaperone. She curled her hands around the unbearably warm mug of English Breakfast to keep them from shaking, forced her feet to stop tapping. This was not supposed to be happening. The police officers were not young, not the mavericks of television shows, but a man and woman in their mid-forties who were unerringly calm and polite.

‘Thank you so much for your time, Mia, we really do appreciate it.’ They punctuated their steady questions with sips of tea. It hadn’t cooled, and must have scalded the soft flesh of their tongues, but they didn’t flicker.

Mia was meek at first; eyes down, voice small. Rachel had scarcely addressed the situation with Mia before the police arrived. They’d hugged so tightly their bones had clashed, but Rachel hadn’t articulated her fears. She didn’t want to hear them out loud. Mia answered the first few questions – about who she was and how she knew Lily – incredibly carefully, as if she might be tripped up, calibrating her age to the month. She looked exhausted. Lines ran from the inner corners of her eyes down to her ears, as if her face had been folded with tiredness. She could scarcely have slept the night before, and the news of Lily seemed to have depleted whatever reserves of energy were left.

‘Okay then, Mia.’ The woman spoke most often, brown hair tucked behind her ears, resting her mug on the round of her knee. ‘We do need to know if Lily seemed different to you over the last few days.’ Her tone was light, as if she was talking to a much younger child.

‘She was the same. She was fine.’

‘She didn’t seem worried at all to you, Mia, like maybe she was nervous about something?’ Each of her questions followed the same sing-song pattern of intonation.

‘No.’

‘Did she mention any plans she had to you, anything she was looking forward to?’ That same flimsy rhythm.

‘No, she didn’t. Can you just tell me where she is?’

‘We’re not sure at the moment, Mia.’ The woman, who’d introduced herself as DC Redpath, kept saying Mia’s name, cooing out those two syllables – mee-aah – like she was stroking her, luring her to tell more. ‘Were there no hints or anything at all we might need to know?’

‘No.’ Mia was definite. ‘I really don’t know what you’re talking about. Just tell me where Lily is.’

The philtrum of her lip was curling upwards, a sure sign she was trying to stop herself from crying. Rachel knew that lip. It curled the same way Tim’s did. That same patch of flesh she’d kissed so often had been lifted directly and transferred to her daughter’s mouth. Rachel couldn’t stand to see it twitch. She wanted to stop them, make them wait. Mia needed to process the news before being interrogated. DC Redpath’s manner didn’t stop it from being a grilling. But they’d been adamant. They wanted the girls’ first reactions, unsullied by too much thought, with no chance for them to conspire. They were making an exception by not asking them to come to the station. Rachel had been grateful for the gesture, but now she wanted to stand up and order them to leave her daughter alone, to leave her house immediately and not come back. She wanted them to take their thoughts with them. She knew the grisliness of what they’d been trained for, of what they were imagining. The smells and the textures. Rachel wanted their statistics, their likelihoods, their blood-soaked practicalities far away from her home. She could only sit with her cooling mug of tea and watch.

The man, DC Scott, finally broke his silence. ‘Mia, whatever you tell us now, however insignificant it seems to you, could be crucial in finding Lily and getting her back home. Did she say anything that we need to know? Do you know where she might be? Do you know who she might be with?’

Mia didn’t answer.

Rachel wanted to hold Mia’s face, focus their eyes on each other and tell her it was okay, that she didn’t need to worry, that Lily would be fine, that no one was in trouble. But Rachel had been superseded by a higher authority. Even in her own home, they were both under a different jurisdiction. She wanted to look into Mia’s eyes close up, not clouded by even a few steps. She wanted to see if there was anything Mia had to tell.

‘Lily has been missing for over twenty-four hours now. This is very serious.’

Rachel tried to blank his words and their implications. It wasn’t serious. It was a mistake. As they questioned her from different angles, repeating the same enquiry over and over, Mia lost her stiff calmness. As they kept trying to winkle out a fresh reply, she became every inch fifteen; stroppy and outraged, raking her hands through her hair. Her voice was louder now. Higher. Faster.

‘Why do you think I know? I don’t know anything. You don’t even know. Why don’t you know where she is? How do you even know if she’s okay?’

The roof of Rachel’s mouth throbbed. Seeing Mia’s distress, but not being able to ease it, was painful. It was all meant to be over by now. Lily was supposed to be at home, tearful and apologetic, tucked up in her purple duvet and eating platefuls of toast made by her mother. There was meant to be nothing left but relieved exhaustion and a hackneyed lecture. Instead, two uniformed officers were sitting on Rachel’s sofa, their black shoes square on her cream carpet.

‘Can you come back?’

It was Sunday where he was too, lunchtime, but she’d still had to summon him from a meeting. She had never interrupted his work before.

‘I’m back in just over week, Rach. It’s not long.’

Rachel paced the kitchen. Three steps one way, then three steps to retrace them. ‘It’s twelve days, Tim. We need you back. She’s frightened. I’m frightened.’

There was a time lag between every utterance. A stutter of silence that hindered their flow. It was technology stretched to its limits, struggling to keep up, or Tim stumbling to form his sentence.

‘I know, sweetie, I know. But I can’t do anything. My being there won’t make her any safer. It might just freak her out more, make it seem more urgent.’

Rachel had to modulate her voice. ‘Tim, her best friend has vanished. She could be anywhere. She could be dead. This is urgent.’

After the blank beat of time, his tone was saccharine. ‘Rach, honey, she’ll be fine. You know that, don’t you? She’ll be back tomorrow and it’ll all be over.’

Rachel let his platitudes coo down the line, eking their way across four thousand miles, barely registering as sounds by the time they reached her ears.

The television was on. It was an HBO drama they’d never watched, deep into series seven. There was a courtroom scene, a woman with immaculate lipstick, then thumping music. It was too bright, too loud. The remote control was on the other side of the room. The screen people began to shout at each other. Rachel had no idea who they were, or why they were upset. She and Mia both watched. They didn’t play with their phones, just faced the screen. It was after ten, but neither of them had made any move to go to bed. Rachel swal

lowed. Words formed in her mouth, swelled to fill it, then sat leaden on her tongue.

The figures on the screen were kissing now, suddenly pawing suits and shirts off each other. Rachel looked at Mia without moving her head. Mia didn’t respond. Rachel remembered the creeping awkwardness of her own parents’ house during a television sex scene – the silence, the personal prayer not to make an inadvertent sigh, the hard stare straight at the floral curtains. She and Mia had always turned it into a joke. Even when Mia was very young, they’d shriek at each other, Don’t look, don’t look, it’s rude. They’d hide their faces in their hands, cover each other’s eyes. They’d squeal if the characters merely shared a chaste peck. It’s rude, don’t look. I’m being corrupted, Mia would yell, I’m morally ruined. She’d been so much fun.

Rachel coughed. The little bark echoed around the living room. Mia didn’t even shift her gaze. ‘You tired yet, Mi?’

Seconds passed before her reply. ‘Not really.’

Rachel wanted to talk. She wanted to turn the television off and sit with her daughter, to hold her, to ask her every question that was clogging her thoughts. But it was so precarious. A single word badly pitched could throw the whole evening. Rachel didn’t know which phrase would make Mia jink like metal on a filling. Mia was curled into the corner of the sofa, tiny in her leggings and hoodie. When she stood, she seemed all limbs, but tucked around herself, her knees hugged to her chest, she was so little again. She was huddled despite the heat, her hands stuffed into her top’s marsupial pouch, her hood up. The circle of her face was the only skin on show.

Rachel wanted to push herself up from the armchair, take the two steps across the room and hold her daughter. She wanted to wrap her arms around that grey hoodie and whisper into the soft of Mia’s ear, coo right into her thoughts, whatever they were, wherever they took her, and tell her she was safe. If she spoke right into her ear, Mia couldn’t slink away. She’d have to hear her mother’s fierce words. Rachel didn’t need Mia to speak; she just wanted to feel her daughter’s shoulder blades dig into her collarbone as she held her. She wanted to push her face into Mia’s hair, and smell the warm salt of her scalp.

With Tim away, Rachel was left to steer every vital conversation, quell every silence, soothe every concern. It used to be so easy. When Mia was small, Rachel had read the articles, heard the whispers at toddler groups. She knew all about the despair other mothers struggled with, the malaise they fought. It sounded terrible, but Rachel had experienced nothing of it. She’d loved those clammy, milky days, that blanketed bubble. She’d loved shutting the door and revelling in the hours alone with her tiny cub.

She tried again. ‘I might head up soon.’

‘Okay.’

She could never pinpoint the day, the exact moment it had altered. They’d sailed through thirteen, and Rachel had grinned with smugness. It happened so gradually, so subtly that it seemed invisible. She noticed it like a new piece of furniture she had no memory of buying. Mia, one day, stood level with her. When they spoke, Rachel’s eyes faced forwards. She could no longer see the crown of her daughter’s head, no longer examine that whorl where her hair began. Suddenly, there were two women in the house. There was a tall, demanding stranger, an interloper who ate her food and flopped over her sofa. Her little comrade had gone, and Rachel felt it as grief. She ached for her girl, and struggled to get used to this new person. Words became complex around her, movements too clumsy. Even now, even when they needed each other.

‘Do you want anything else to eat?’ She spoke the lines of the bland mothers she’d sworn never to be. She cringed as the words landed. ‘Cup of tea?’

‘I’m fine.’ Mia stood up, unfurling those endless legs and arms. Rachel tried to reach her as she left the room, tried to stroke the marl of her hoodie, grip the flesh beneath it, but Mia wisped by and vanished upstairs. Her phone was in the folds of grey material, and she’d text her friends, her boyfriend, as soon as she was alone. Rachel wanted to follow her. She wanted to keep her in sight. They used to curl up together in the evenings Tim worked late, a pile of snacks on the coffee table, watching films Mia was far too young for. Rachel had always been proud of being permissive. They’d plait each other’s hair as the movies flashed in front of them. Rachel would carry Mia up to bed when she inevitably dropped off. There must have been a night in that dark room – Rachel struggled to conjure back the sense memory – when she’d placed Mia down and never picked her up again.

With Mia upstairs, Rachel was alone. The house had far too much space when it was just them. It seemed mocking in its airiness; only two figures to fill its family-sized expanses. The boundaries of Rachel’s body felt too definite. No hands had touched her skin for so many days. She’d spend too long in the shower just to feel its spray on her muscles.

That night, the house echoed; its shadows loomed deeper. Nothing felt familiar. The woollen throws they draped over the sofa felt cloying; their curtains seemed to trap the air. Heat brewed in every room with no escape. The house felt foolish – a charade of safety. It was just an insubstantial construct of bricks and wood. Just because the door needed three keys to be opened didn’t mean it couldn’t be torn from its hinges in a second. Mia felt too far away to protect. Rachel had to be upstairs with her. Lily was out there somewhere, not safe in her bed. Rachel stood outside Mia’s room. She sank slowly to her haunches, until her back pressed against the door. Was Mia awake on the other side of that painted wood? Was she wide-eyed and terrified for her missing friend? Was she frightened of what might come splintering through the glass of her window and drag her away for ever? Or did she sleep soundly? The floor was the coolest place in the house, and the air felt easier there. Rachel didn’t blink. In that position, in that dark, she spent the whole night, silently guarding Mia’s door.

Rachel dropped Mia off before school for the first time in years. The night had blurred into Monday morning, and Rachel’s eyes pulsed with lack of sleep. The temperature had already risen to irritable levels. Rather than let Mia walk, they drove to Keira’s. There would be no other pupils at school for an hour, and she couldn’t leave Mia alone, not until Lily was safe. Keira’s house was in the neighbouring cul-de-sac, almost identical to theirs. Rooms in the same places, bricks laid in the same year, the same honeysuckle trailing over the doorway. The smell was thick even so early in the morning. When Keira’s mother, Marianne, opened the door, Rachel had an overwhelming desire to hug her, to sob in her arms. Instead, they exchanged stiff smiles.

‘You’ll call if you hear anything at school, won’t you, Rachel?’ Their voices were tight, acting the roles of calm adults with nothing to fear.

‘Absolutely. Of course. If I hear anything at all. I’m sure Lily’ll be in touch today, and feel terrible for putting us all through this.’

Marianne’s grin had no light. ‘Then we can have her guts for garters.’ They both flinched at the image.

The girls nodded, solemn. Their faces were unusually free of make-up. They were bare of their perennial crayoned eyebrows and sculpted cheeks, and it made them look peaky. Rachel tried to catch Marianne’s eye when the girls weren’t looking, to allow them a flash of the horror they both felt, but Marianne stared straight ahead.

Rachel’s days were front-weighted. She grabbed at the crisp hours to plan. It was the only chance she had to gain mastery over her workload. And she hated the school at night; hated being alone in a dim corridor. She’d do anything not to leave last. Steps echoed more in the darkness, after the cleaners locked up and turned off the buzzing halogen lights. Schools were full of unexpected noises – trainer squeaks, coat friction, books slipping from shelves. It could be terrifying. The daytimes had their own form of mania, and mid-June marked their high point, as exams drew to a close. Even the pupils who stood years away from their GCSEs seemed irritable, a premonition of the stress that would descend. The whole school seemed fractious once that first bell had rung, and the heat just

ratcheted it up.

The early mornings were different. Seven-thirty could feel like dawn. Pale light would fill the corridors; great shards of light, so perfect their edges could cut, would fall from the upper windows. There was peace. The eucalyptus detergent used overnight lingered, masking every other smell that would later taint the place. That morning it felt like a benediction. Rachel inhaled the scent as if it could strip away the terror, the hideous thoughts she couldn’t fend off; as if it could clean her lungs, cleanse her thoughts, and make everything pure again.

The head walked in and stood, hands steepled, until the room eventually scuffled to silence. It took nearly a minute.

‘Thank you for coming in so early today.’ They’d been called to the staffroom before registration. Rachel stood near the back wall, close to the door, where she hoped it might be cooler. The room had filled quickly, bags littering the floors and papers spilling across every table. The last weeks of summer term should feel like respite, a simple counting-down of days, but the tension of those teenagers infected everything. They walked around, pale and taut. The sun felt like a bad spirit, urging them to lethargy just as they most needed alertness. It left everyone jittery.

A handful of teachers, mostly maths and science, were using the end-of-term class schedules to attend training courses, but everyone else was crammed into the same room. They were gathered in small clutches, speaking in low voices with wide eyes. Rumours had already whipped around, but no one knew anything solid. Rachel didn’t speak. At eight o’clock, the heat in that packed room was already punishing. The men were still in shirtsleeves, the women in full shoes. The windows were not opened.

Heatstroke: an intoxicating story of obsession over one hot summer

Heatstroke: an intoxicating story of obsession over one hot summer